“The river is dry because everybody’s taking water out”, says Austin. “We’re putting water in.”

Austin’s Rancho El Coronado, not far from famed 19th Century Indian leader Cochise’s mountain stronghold, and Rancho San Bernardino, spanning the international border near Douglas, Arizona, and Piedras Negras, Sonora, are Cuenca Los Ojos’ project sites for reviving the Rio Yaqui.

They were once ciénagas, or swamps, as indicated by the telltale dark silty talcum powder like soil. They are part of a once-vast wetland, now reduced to a fraction of its former self by poor land use practices, such as lumbering in the mountains and cattle ranching in the valleys.

“We’re trying to raise the level of stream beds so water will overflow again, spread out, and plants associated with the ciénaga will start coming back,” says Austin.

“It was dry where we are, and now there are three miles of water running through Rancho Coronado. There is water year round in the river. The land holds it like a sponge. The sponge becomes more and more beneficial for the whole Rio Yaqui system. You want to get the whole river to do that.

A century after Geronimo, CLO sent out teams to construct loose rock structures up hillsides and to shovel up earth berms with heavy machinery in order to plug erosion and capture water. This serve the purpose of slowing down the runoff from monsoon rains and catching sediment that would otherwise wash away.

They built larger dam-like structures called gabions by filling wire baskets with rocks. Eventually the gabions became buried and the riverbed was raised. Now each year the gabions are being built higher. The sediment is expected to collect enough for water to spill over the surface of the terrain, re-forming the wetlands.

Austin’s concerns are for the long term and the big picture.

By Talli Nauman*

Sonora Gov. Guillermo Padres Elias’ bid to divert drinking and irrigation water from the Yaqui River Basin to industry in the state’s capital city of Hermosillo is an affront, not only to indigenous and farming communities downstream from the Novillo Dam, but also to conservationists upstream across the U.S.-Mexico border in Arizona.

Unbeknownst to the Yaqui Tribe and the Yaqui River Valley farmers, who are desperately fighting to keep the Sonora state government from appropriating the flow from their watershed, the Cuenca Los Ojos (CLO) Foundation, high in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeast Arizona, has been working feverishly for 30 years to replenish the headwaters of the Yaqui River.

“We have restored 20 percent of the original ciénaga,” CLO co-founder Valer Austin told Meloncoyote.

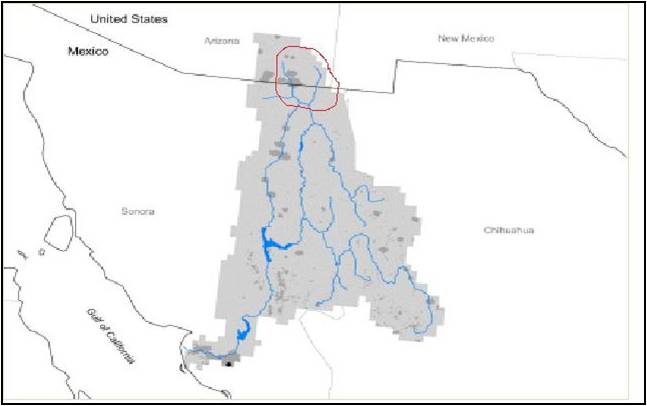

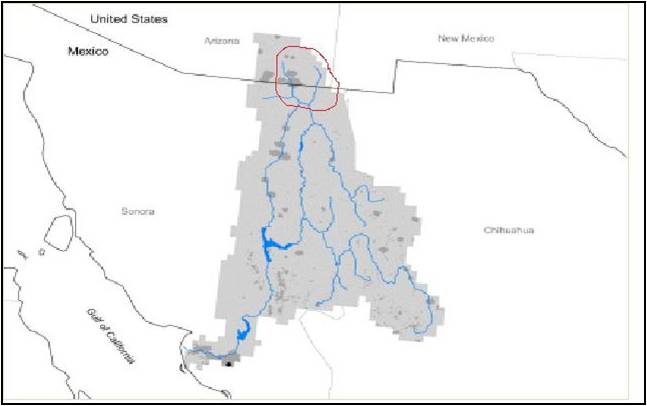

The Yaqui Basin is the largest river system in Sonora. The river runs approximately 320km (200mi) through the state to the Gulf of California.

Along much of the length of the binational river, no water can be seen in its sandy bed. What’s there is only enough to flow underground in the channel. Evidence of desertification is clear in the many dead trees standing and fallen along the river banks.

"I’m thinking 200 years down the road” she says. “It’s systems you have to think about. For climate change, a swamp in a desert is very, very important. A swamp will hold more water than a narrow channeled river. “Trees transpiring are forming clouds. At the same time they’re holding water in the moist and shady area below their branches,” she says.

“What if we could take this system and use it on the Rio Yaqui and everywhere in the whole world?” she says.

With that in mind, she is forging links, which now encircle 25 organizations in the Yaqui-Gila Watershed Alliance. Their objective is to protect migratory routes for animals and birds that travel between Costa Rica and Canada.

Among groups involved in this crossborder initiative are the Animas Foundation, the Malpai Borderlands Group, The Nature Conservancy, Sky Islands Alliance, Wildlands, Naturalia, Pronatura, and the Northern Jaguar Project. On the part of the governments, Mexico’s National Protected Natural Areas Commission and its National Forestry Commission are involved, as well as a number of U.S. Interior Department agencies.

*Codirector, Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness

The hard work began with the placement of rocks in the creek beds...

... and then progressed to the construction of large gabions, wire basket structures filled with rocks.

Cuenca Los Ojos is working inside the area outlined in red, within the greater Yaqui River Basin showin in gray. (Map courtesy of CLO)

Cuenca Los Ojos is working inside the area outlined in red, within the greater Yaqui River Basin showin in gray. (Map courtesy of CLO) Cuenca Los Ojos is working inside the area outlined in red, within the greater Yaqui River Basin showin in gray. (Map courtesy of CLO)

Cuenca Los Ojos is working inside the area outlined in red, within the greater Yaqui River Basin showin in gray. (Map courtesy of CLO) Valer Austin (Photo: Talli Nauman)

Valer Austin (Photo: Talli Nauman)  Austin on trail at Rancho El Coronado. (Photo: Talli Nauman)

Austin on trail at Rancho El Coronado. (Photo: Talli Nauman)